The Hobbit (1977)

The Hobbit (1977) is a curious beast. It’s a made for television animated film, which despite its budgetary constraints, strives to comprehensively adapted one of the most beloved children’s books of the last century. I remember reading an article about this television adaptation of The Hobbit, in Starburst Magazine during the late seventies. There were rumours that this Rankin/Bass production, which had already premièred on US network television, would gain a European cinema release. This was presumably to cash in on the success of Ralph Bakshi's animated feature film adaptation of The Lord of The Rings. However, this never happened to my knowledge. In fact, The Hobbit was not commercially available in the UK until 2001, when Warner Bros. released it on DVD to capitalise on the success of Peter Jackson’s The Fellowship of the Ring.

The Hobbit (1977) is a curious beast. It’s a made for television animated film, which despite its budgetary constraints, strives to comprehensively adapted one of the most beloved children’s books of the last century. I remember reading an article about this television adaptation of The Hobbit, in Starburst Magazine during the late seventies. There were rumours that this Rankin/Bass production, which had already premièred on US network television, would gain a European cinema release. This was presumably to cash in on the success of Ralph Bakshi's animated feature film adaptation of The Lord of The Rings. However, this never happened to my knowledge. In fact, The Hobbit was not commercially available in the UK until 2001, when Warner Bros. released it on DVD to capitalise on the success of Peter Jackson’s The Fellowship of the Ring.

Rankin/Bass productions had a pedigree in bringing traditional and familiar children's material to the small screen, with such titles as Frosty the Snowman and Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, so it was not unusual for them to take on such a project. However, a lot of the animation was sub contracted to Japanese studios, which was a standard practise at the time. This subsequently had a major impact on the production design and the aesthetics of the film. Rankin/Bass productions often included songs in their commercial output as it had proven to be a major selling point in the past. Naturally, original Tolkien's work with its abundance of songs and verse, lent itself to this very well. As a result, The Hobbit has a wealth of vocal tracks sung by popular folk singer, Glenn Yarbrough. They’re not to everyone’s taste but they do work, and some do stick quite faithfully to the source text.

The adaptation of the story is very simple. Some of the more complex plot details have been lost, such as the Arkenstone of Thrain, the skin-changer Beorn and the scheming master of Lake Town. Tolkien wrote this story for children and that is the way the film’s screenplay is pitched. The character designs range from the adequate to the bizarre. Gandalf is represented pretty much as you would expect, sticking to the usual old man with a pointy hat trope. Bilbo and the Dwarves reflect a more juvenile friendly interpretation. However, the Trolls and Goblins are not especially scary and lack any real sense of threat. It is in the design of the Elves that this production really fumbles the ball. This race of near perfect creatures with their angelic qualities, are simply ugly and emaciated. Someone definitely failed to understand the source text in this respect. Gollum is also poorly conceived and looks a little like a large Bullfrog. And all I'll say about the dragon Smaug, is that his feline quality is "unusual".

With these shortcomings, are there any positive attributes regarding this production? Well the minimalist water colour backgrounds work well, often drawing on Tolkien’s illustrations themselves. The voice casting has some strong performers, such as John Huston as Gandalf. However, some of the minor characters are played by well-known voice artists Don Messick and John Stephenson. As a result, you do feel that you’re watching an episode of Scooby Doo or The Arabian Nights at times. So where does this leave us? Well it's difficult to be objective, as any adaptation of Professor Tolkien's work tends to be over shadowed by the success of Peter Jackson's two trilogies, which have established an aesthetic standard. Therefore, this older version of The Hobbit suffers as a result, as it flies in the face of this. Overall, it’s a low budget, basic adaptation, with a variety of good and bad animation. It will probably find its most appreciative audience, among children, for whom it was intended.

Shadow of War: Grinding to a Halt

After fifty plus hours of playing Middle-earth: Shadow of War, I have finally ground to a halt, in more ways than one. I have completed the Gondor, Shelob, Eltarial and Carnán quest lines, as well as the Brûz and Nemesis missions. I have also unlocked all the skills gained from the Shadow of the Past session play. Over the course of a fortnight, I’ve tackled all the “busy work” sub missions, such as the collectable Gondorian artefacts and Shelob’s memories. My approach to Middle-earth: Shadow of War has been very focused and methodical. As a result, I have conquered all the regions that are currently available. Each fortress is populated by epic level Orcs that are loyal to the “Bright Lord”. Overall, it has been a very enjoyable experience, although the quality of gameplay has been somewhat inconsistent. Middle-earth: Shadow of War has several flaws and the endgame is one of them.

After fifty plus hours of playing Middle-earth: Shadow of War, I have finally ground to a halt, in more ways than one. I have completed the Gondor, Shelob, Eltarial and Carnán quest lines, as well as the Brûz and Nemesis missions. I have also unlocked all the skills gained from the Shadow of the Past session play. Over the course of a fortnight, I’ve tackled all the “busy work” sub missions, such as the collectable Gondorian artefacts and Shelob’s memories. My approach to Middle-earth: Shadow of War has been very focused and methodical. As a result, I have conquered all the regions that are currently available. Each fortress is populated by epic level Orcs that are loyal to the “Bright Lord”. Overall, it has been a very enjoyable experience, although the quality of gameplay has been somewhat inconsistent. Middle-earth: Shadow of War has several flaws and the endgame is one of them.

Compared to the previous game, there is a degree of skills bloat this time round. Some do seem somewhat superfluous, such as the ability to poison kegs of grog from range. However, picking the right skills for your playstyle and gear build is key to success. Some of the skill modifiers are essential and give the player a distinct advantage. Freeze Vault and Shadow Strike variants (especially the one that summons the target towards you) help immensely. It should be noted that combat is more complex this time round. The higher density of enemies makes stealth far harder. Taking the high ground and considering your next move helps immeasurably. At street level, especially in the fortresses it is very easy to become overwhelmed by enemies at times. Freeze Pin, Elven Fire and Rage can be used tactically to subdue a primary target and then clear swarming enemies. As with the previous game, running away if things get out of hand is a valid tactic. Summoning a body guard or a dominated beast can also be fun, although flying a Drake with a keyboard is not exactly easy.

The third act of the game, is a series of Siege Missions which are especially gruelling. Initially these are quite engaging as you plan your tactics and equip your assault force with suitable skills. But there are ten stages to this part of the game, where you repeatedly defend your five major fortresses. Naturally, the difficulty increases the further you progress as well as the duration of each siege. It does become a little repetitive towards the end and you feel at times like you’re simply plugging holes in a dike. You go from capture point to capture point holding back the enemy and healing your high-level orcs. There is often a tipping point where you know that events have gotten beyond your control and you can feel the battle slipping away from you. Hence there is an element of monotony to this part of the game and if you’ve already cleared all the other quests in the game, it can feel like a treadmill.

During the course of my play through, I’ve also made some basic errors that have now come back to inconvenience me. One of these being the equipment challenge which allows you to upgrade specific legendary gear. One of the easiest sets to obtain in the game is the Bright Lord armour which is gated behind Ithildin doors. There are word puzzles to solve to open them. I obtained this set quite early on in the game and the gear scaled to the level I was at the time. To upgrade the gear, I had to recruit specific Orc captains. However, by this time I had killed, replaced or seeded all relevant enemies in the region and was unable to find any Orcs that met the criteria. The only way to resolve the issue would be to kill my dominated Orcs and allow new ones loyal to Sauron to spawn. As I didn’t relish this prospect, I simply collected another legendary armour set, via the vendetta system. As I am now at level cap, the gear drops where of a comparable rating.

The lore breaking story of Middle-earth: Shadow of War is very inventive but a bit farcical at times. It really does play fast and loose with the established canon and flat out contradicts it at times. But despite these transgressions it is still quite enthralling. The nemesis system and the personalities of the various Orc are still at the games core. However, the endgame suffers due to the gating of Orcs behind loot boxes. As a player you have far less of an emotional connection to an Orc that you’ve literally just obtained from a crate, over one that you’ve fought, dominated and grown accustomed to. Furthermore, even the top tier Orcs that fight for you are somewhat squishy. Pit fights also are far from an exact science and I’ve lost some über Orcs to surprisingly low-level enemies. Integrating a cash shop into this part of the game has clearly had a detrimental effect upon the final act of Middle-earth: Shadow of War.

I have now reached the stage where I shall take some time out from Middle-earth: Shadow of War. As previously mentioned, the last stage of the game has been a bit of a grind and I would rather wait now for further content to be released, rather than kill my passion by just pottering about achieving nothing in particular. The release time table for the DLC was announced yesterday and it would appear that there’s no further narrative driven content until 2018. I don’t mind new Orc tribes to conquer but I do prefer story based content over simple achievements. I don’t regret pre-ordering the game, as it has been fun to participate in an event as it happens. However, if Shadow of War follows the pattern set by Shadow of Mordor, then a drop-in price may well occur by the end of the year. Certainly, buying the game at a discount will help compensate for the weak areas in the gameplay.

Killing Orcs and Taking Names

Middle-earth: Shadow of Mordor unlocked on Steam at 6:00 PM today and within minutes I was back in Mordor murdering Orcs once again. It is interesting sequel, to say the least. First off, I’ve not seen quite as much mainstream publicity for a game for a while. There has been a fair amount of TV advertising and every London Bus I see, seems to be adorned with promotional posters for the game. Next, this game is acutely aware that it’s a sequel and does everything it can to improve and embellish upon the previous instalment. Such a policy broadly works but there are times when there seems to be an overabundance of choice. Many of the core skills from the first game make a return but have a subset of modifiers. Not all of them seem that important or relevant. However, the new double jump is invaluable for navigating the environment which features numerous iconic locations such as Minas Ithil and Cirith Ungol. There’s also a far greater number of mobs about this time so stealth is not always an easy option.

Middle-earth: Shadow of Mordor unlocked on Steam at 6:00 PM today and within minutes I was back in Mordor murdering Orcs once again. It is interesting sequel, to say the least. First off, I’ve not seen quite as much mainstream publicity for a game for a while. There has been a fair amount of TV advertising and every London Bus I see, seems to be adorned with promotional posters for the game. Next, this game is acutely aware that it’s a sequel and does everything it can to improve and embellish upon the previous instalment. Such a policy broadly works but there are times when there seems to be an overabundance of choice. Many of the core skills from the first game make a return but have a subset of modifiers. Not all of them seem that important or relevant. However, the new double jump is invaluable for navigating the environment which features numerous iconic locations such as Minas Ithil and Cirith Ungol. There’s also a far greater number of mobs about this time so stealth is not always an easy option.

As with the previous game, if you’re a Tolkien purist then you may object to some of the liberties that the writers have taken with existing lore. Talion is still connected to the spirit of Celebrimbor and the game starts with the forging of a new ring, free from the power of Sauron. However, the crafting process weakens the Second Age Ñoldorin prince and he is separated from Talion. The Grave Walker eventually tracks him down, finding him in the clutches of Shelob. She will release him only if Talion freely gives her the new ring. As he has no other option Talion agrees and Celebrimbor is restored to him. Shelob encourages them to make war upon Sauron and suggests that the Palantir of Minas Ithil will aid them. However, Sauron has plans of his own and lays siege to the Tower of the Moon. Celebrimbor deems the city lost but Talion feels obliged to fight with his people. However, will the pair of them be able to withstand the Nazgûl and their leader the Witch-King of Angmar.

It's a bold narrative despite the canonical inconsistencies. Minas Ithil fell to the Nazgûl 939 years earlier in the third age but to be honest it doesn’t really matter. This is a game set more in Peter Jackson’s version of Middle-earth, rather than Tolkien’s. And once again it is the nemesis system that is the major selling point. The Orcs, Uruks and Ologs all have incredibly well written personalities and can be either sinister, repulsive or just plain crazy. They often have curious quirks and foibles that come dangerously close to parody but the humour is kept on the right side of the line, so it doesn’t get too silly. The game also has a wealth of minor quests and collectables, that some would describe as busy work. There are dozens of lore items to discover, each with a short-narrated anecdote connected to them. Then there are fragments of Shelob’s memory to collect. Furthermore, this time round there is gear to collect and upgrade.

So far, it all seems highly polished and very familiar. Having maxed out my previous character in the last game it is a little odd to be starting from scratch again and to be missing many of the skills I came to rely puon. They all have to be earned from scratch again. At present I cannot dominate Orcs and so I have had no reason to look any further in to the Fortress Siege system. I’m not required for the meantime to recruit an army to rival Sauron’s. I suspect that mechanic will be part of the endgame along with the requirement to use the loot box system. Exactly how long it takes to get there, is a subject of interest to me. The marketing of Middle-earth: Shadow of War suggests there is fifty to sixty hours of gameplay in the campaign. Considering that I spent £59.99 for the Gold Edition of the game, I hope that is the case. As and when I have to use the microtransaction mechanic in this game, I will write another blog post to discuss how I find it. For the present I will simply say, so far, so good.

Is Shared Fandom a Bridge to Reconciliation?

There are and always will be books that have a clear political agenda or make a very particular statement. Orwell’s 1984 springs to mind as an obvious example. Then there are also books that attract political interpretations by the nature of their plot or the subjects that they explore. Whether the author intended such a debate about the work or not, is a secondary issue. I have always taken Tolkien’s work at face value and to be what he stated they were. Epic and intricate faux histories, free from allegory. Furthermore, I appreciate that the moral position and themes of his work stem from the authors world view, personal experiences as well as the prevailing social dogma of the time. I find it interesting how his work attracts praise and adulation from a wide variety of groups. Catholics will naturally gravitate towards Tolkien’s writings due to his faith and that is the prism through which they will critically view his work. There are of course other examples about how The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings appeals to different people in different ways. It is a common aspect of fandom.

Fandom by Tom Preston

There are and always will be books that have a clear political agenda or make a very particular statement. Orwell’s 1984 springs to mind as an obvious example. Then there are also books that attract political interpretations by the nature of their plot or the subjects that they explore. Whether the author intended such a debate about the work or not, is a secondary issue. I have always taken Tolkien’s work at face value and to be what he stated they were. Epic and intricate faux histories, free from allegory. Furthermore, I appreciate that the moral position and themes of his work stem from the authors world view, personal experiences as well as the prevailing social dogma of the time. I find it interesting how his work attracts praise and adulation from a wide variety of groups. Catholics will naturally gravitate towards Tolkien’s writings due to his faith and that is the prism through which they will critically view his work. There are of course other examples about how The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings appeals to different people in different ways. This is a common aspect of fandom.

Bearing this in mind, it should not come as surprise to learn that Tolkien’s writing also has fans among the political class. The UK Conservative Party MEP Daniel Hannan is one who has written essays on his love of the Professor’s work and its literary merits. For example, Mr Hannan says “Here is a book that, as much as any I can think of, needs to be read aloud. Tolkien, like many Catholics of his generation, understood the power of incantation. He knew that—as, funnily enough, Pullman once put it—a fine poem fills your mouth with magic, as if you were chanting a spell”. Upon reading more of his analysis of Tolkien’s work, it becomes apparent that several of his political colleagues share his passion. It would seem many Conservative MPs find that Tolkien’s writing contains themes and concepts that they equate with their political ideology. Curiously enough what they see in the Professor’s work, I have never experienced. Again, they view it and quantify it in a different way to myself. This raises some interesting points about when you discover that you share a liking for something with a group you didn’t expect.

I suppose the optimistic way to interpret this situation is to focus on how fandom can build bridges and that there is now theoretically common ground between both parties concerned, despite their obvious differences. However, I feel that it’s a more complex situation than that. In this instance, I do not hold with a lot of the opinions and world view of this particular group of people. I think that many of the policies that the Conservative party have implemented since they came to power in 2010, have been harmful to both individuals and to society. Therefore, does simply having a shared passion for one specific thing bridge an otherwise, vast cultural, philosophical, political divide? I do not think that it does. If I were to meet Mr Hannan in a social situation, I would endeavour to be civil to him and focus on our common ground but ultimately our shared love for Tolkien is not a path to reconciliation. He would still remain at odds with my political sensibilities and continue to be a Conservative party member.

Reflecting upon this example and other comparable ones, certainly raises some interesting questions. It is a timely reminder that fandom does not give you any sense of ownership towards the object of your affection. Nor do you get to decide who can like or not like the thing in question, or who are “true fans”. The reality is that what appeals to you about the thing you love, is not necessarily the same for everyone and that we all interpret and respond to art as well as literature in a different way. Furthermore, when you do find out that you share a common love for something with those who are radically different to yourself, their presence should not spoil that very thing for you. Irrespective of the fans and their differences, the object of affection (in this case Tolkien’s writing), remains untouched. Overall, I guess this matter is a timely reminder about tolerance and sharing.

The analogy that springs to mind is one regarding religion, specifically Christianity. It is a faith that is rife with different denominations. All allegedly cleave to the same fundamental principles, yet interpret the scriptures differently. Is this situation about the differences between fan bases not dissimilar to the divide between Anglicans and fundamentalist Evangelicals? Also, history shows that many fine things have been liked, embraced or advocated by the morally questionable. So, it would appear that a shared love is not an assured ticket to harmony and reconciliation. The divided nature of the gaming community is an ongoing testament to that. The fallout over the recent casting of a female actor as Doctor Who is further proof that fandom is a broad but far from united church. As for Tolkien, I shall simply content myself with my own personal enjoyment of his work and leave others to do so in their own way. However, what I will not allow unchecked is for others to usurp his writing and claim it justifies something that it empirically does not.

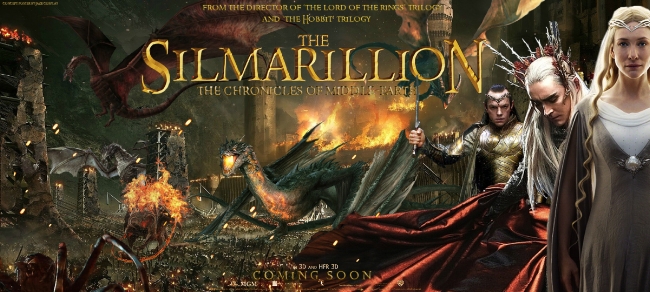

The Silmarillion Movie

When Peter Jackson finished filming The Hobbit trilogy, there was some idle speculation by fans as to the possibility of a movie adaptation of The Silmarillion. It was meant mainly as a talking point, rather than a serious proposition and there certainly was an enthusiastic response from some quarters. Three years on, the fantasy genre is still a commercially successful genre both at Cinemas and on TV. Furthermore, production studios are regularly looking to existing literary properties that they can convert into viable long term franchises. Bearing all this in mind, is it possible that Tolkien’s complex mythopoeic work could be adapted for either the big or little screen?

When Peter Jackson finished filming The Hobbit trilogy, there was some idle speculation by fans as to the possibility of a movie adaptation of The Silmarillion. It was meant mainly as a talking point, rather than a serious proposition and there certainly was an enthusiastic response from some quarters. Three years on, the fantasy genre is still a commercially successful genre both at Cinemas and on TV. Furthermore, production studios are regularly looking to existing literary properties that they can convert into viable long term franchises. Bearing all this in mind, is it possible that Tolkien’s complex mythopoeic work could be adapted for either the big or little screen?

Although it is theoretically possible to make either a movie of TV show from the source material, the likelihood of such a project coming to pass is very remote. Hollywood studios are very risk averse, especially towards material that cannot be easily defined and pitched at the broadest demographic. Even if The Silmarillion were to be championed by a major director, there is no guarantee that such a project would be immediately green lit. Hollywood heavy weights such as Steven Spielberg and Martin Scorsese have fallen foul of this policy recently. However, if a Silmarillion adaptation could secure financing, let us consider some of the other potential obstacles that would have to be addressed before the project could move forward.

First, there is the fundamental issue of the rights to The Silmarillion, which are not included in those currently held by Middle-earth Enterprises. I think the Tolkien estate would move heaven and earth to block such a project from progressing, as Christopher Tolkien has made his views very clear on the existing movie adaptations of his father's work. He abhors what he sees as the Disneyfication of the source material. Therefore, this is an issue that cannot be addressed during his lifetime. Whether the heirs to the estate would think differently remains to be seen.

Then there is the source text of The Silmarillion itself, which would be would be extremely difficult to adapt and market to a mainstream audience. It would require considerable restructuring and frankly a lot of dumbing down to make an accessible narrative. It is episodic by nature with an excess of characters and explores a great deal of abstract concepts. There are certainly passages of the text that would make epic set pieces but overall the narrative does not support the traditional three act story arc that cinema prefers.

This then raises the question, rather than a series of movies, would a high budget cable show such as Game of Thrones, be a more suitable medium to showcase The Silmarillion. Either way, a live action adaptation would require a prodigious budget. Considering the philosophical and theological elements to the text, perhaps live action is not the best approach to adapting the work. Would the medium of animation be more appropriate? By this I do not mean mainstream CGI but something more traditional such as cel animation or perhaps some experimental stop motion method?

Then there is the risk that any adaptation may be usurped and extrapolated into something very different from Tolkien’s vision. Tolkien was a devout Catholic although this is not immediately obvious in his works. He also deplored the use of allegory as a literary device. There is a chance that whoever adapts The Silmarillion could colour it with their own personal religious, moral and philosophical baggage and make it into something that it is not. I would hate to see something as cerebral as this book, distilled into a clumsy and misplaced metaphor to be championed by the wrong sort of Christian institutions. The Silmarillion deserves better than that.

If we still consider such a project in movie terms, then it would require director of immense cinematic skill and vision. Peter Jackson, although visually talented, is not the film maker he was a decade or two ago. He is too big a name, too commercial and now appears to exhibit a degree of self-indulgence that often comes when directors become celebrities. Personally, I think his better work is now behind him. A true visionary would be required for The Silmarillion movie but these are a scarce commodity these days. Kubrick, Kurosawa and their like are long dead, so who exactly does that leave? Guillermo del Toro, Bong Joon-ho or Alfonso Cuarón?

As you can see, these are just a few potential problems that would plague such a project. Furthermore, it can be cogently argued that just because you can do something, it doesn't mean that you should. The Silmarillion may well be unfilmable in any meaningful way and to attempt to do so may well be disrespectful to the source text. Unfortunately, film makers and especially their financiers seldom understand such concepts and often end up debasing great literary works in pursuit of the lowest common denominator and box office gold. The Silmarillion was intended by its author to be a book and nothing more. Does it really need to exist in any other way?

The Lord of the Rings - BBC Radio Adaptation (1981)

In 1981 BBC Radio 4 produced an ambitious adaptation of The Lord of the Rings, presenting Tolkien’s novel in twenty six, thirty minute episodes. As with all adaptations some material had to be removed, but overall the BBC production was not excessively abridged and followed the plot faithfully. The characterisations and dialogue were extremely well realised and music by composer Stephen Oliver was very much in the style and idiom of Tolkien. This was a production of the highest pedigree and a major event for the BBC at the time. The series was heavily promoted, receiving front page status in The Radio Times, the UK’s premier TV guide and bestselling magazine. Although initial reviews were varied, the series immediately gained a cult following with fans trading episodes recorded on cassette tape. Word of mouth and substantial listening figures soon lead to revised opinions from the press, along with the immortal slogan "Radio is Hobbit 4-ming".

In 1981 BBC Radio 4 produced an ambitious adaptation of The Lord of the Rings, presenting Tolkien’s novel in twenty six, thirty minute episodes. As with all adaptations some material had to be removed, but overall the BBC production was not excessively abridged and followed the plot faithfully. The characterisations and dialogue were extremely well realised and music by composer Stephen Oliver was very much in the style and idiom of Tolkien. This was a production of the highest pedigree and a major event for the BBC at the time. The series was heavily promoted, receiving front page status in The Radio Times, the UK’s premier TV guide and bestselling magazine. Although initial reviews were varied, the series immediately gained a cult following with fans trading episodes recorded on cassette tape. Word of mouth and substantial listening figures soon lead to revised opinions from the press, along with the immortal slogan "Radio is Hobbit 4-ming".

The trilogy was adapted for radio by the then novice writer Brian Sibley and veteran dramatist Michael Bakewell. It was directed by Jane Morgan and Penny Leicester, who were both experienced in radio dramas. The cast was made up of numerous fine British actors and voice artists such as Ian Holm as Frodo Baggins, John Le Mesurier as Bilbo Baggins and Sir Michael Horden as Gandalf. It also featured Robert Stephens as Aragorn and Peter Woodthorpe as Gollum. The adaptation excised a lot of the "excess fat" from the source text allowing the actors to concentrates on plot, character development and atmosphere. The attention to detail of this production was extremely high with Christopher Tolkien approving the scripts, leading to an authentic depiction of Middle Earth. Great care was taken with pronunciation of words and the delivery of dialogue spoken in Elvish and the Black Speech.

Upon its initial release each of the original twenty six episodes received two broadcasts per week, this remains standard practice for many BBC radio serials. After a successful first run the twenty six part series was subsequently edited into thirteen hour-long episodes, restoring some dialogue originally cut for timing, re-arranging some scenes for dramatic impact and adding linking narration and music cues. The re-edited version was released on both cassette tape and CD boxsets during the eighties and nineties and included bonus material such as the Stephen Oliver’s complete soundtrack for the series. It is this version of the BBC adaptation that has proven most popular and has been most commonly distributed and syndicated over the years.

In 2002 due to the commercial success of Peter Jackson's cinematic adaptations of The Lord of the Rings, the BBC re-issued a revised version of their 1981 series. This comprised of three CD sets corresponding to the three original book volumes (The Fellowship of the Ring, The Two Towers and The Return of the King). This version omitted the original episode divisions and included a new opening and closing narration recorded by Ian Holm. The re-edited version also included some additional music cues. However some fans felt that the re-arranging the material in this way actually spoilt the drama and the flow of the narrative. The original edit of the radio series was constructed so that the separate stories of Frodo and Sam ran in parallel to that of the rest of the Fellowship. It heightened the drama and afforded listeners a clearer understanding of the time line.

Tolkien's linear style proved to be a good fit for radio, with Sibley and Bakewell’s adaptation confidently staying true to the source text. Like Peter Jackson’s movies, some story elements have been cut, such as Tom Bombadil, along with the journey through the Old Forest and the Barrow Downs. However the Scouring of the Shire has been included, ensuring that Tolkien’s codicil is in place and therefore ending the tale correctly. One of the reasons this particular adaptation was so successful was due to the care and attention spent on the voice casting as well as the prudent use of music and song. Tolkien went to great pains to make both language and verse and integral part of Middle-earth and Sibley and Bakewell did not shy away from exploring this facet of the story. The BBC Radiophonic workshop also provided some pertinent sound effects and ambient sounds. As a result both the One Ring and the Nazgul have their own distinct audio characteristics.

Because the production elected to intercut the separate storylines to facilitate a more familiar style of narrative, there was a requirement to bridge a few expository gaps. Writers Brian Sibley and Michael Bakewell tackled this issue in an innovative fashion, adapting text from Tolkien’s later book Unfinished Tales which subsequently explained these literary grey areas. For example during the Nazgul’s quest for the One Ring, they visit Isengard and challenge Saruman over the whereabouts of The Shire. He advises them to pursue Gandalf. However as they follow Mithrandir’s trail they chance upon Grima Wormtongue, who is hurrying to Isengard with a message. It is he that gives up the location of the Shire upon threat of death. These narrative additions help with the flow of the story without breaking the lore.

This exceptional adaptation still remains accessible to both established Tolkien fans and those who have yet to read the trilogy. It is also a quintessential example of BBC Radio drama at its best. Although I enjoyed Peter Jackson’s movies upon their initial release, I feel that the BBC radio adaptation, despite being a different medium, is the better of the two. Peter Woodthorpe’s Gollum is a far more nuanced and sinister portrayal than Andy Serkis’s bi-polar performance. Also Jack May’s King Theoden is far more sympathetic and regal than Bernard Hill’s. Apart from reading the source text, this is the next best way to lose oneself in Tolkien’s classic story. It allows the listener to enjoy the outstanding vocal performances while conjuring up their own depictions of the characters in their mind’s eye. Where Peter Jackson’s movies are very much his interpretation of Middle-earth, the BBC radio adaptation of The Lord of the Rings is a far more faithful and nuanced dramatisation. Due to the medium of radio the strong story and characters are not overwhelmed or marginalised by spectacle.

The Lord of the Rings - The John Boorman Adaptation

n 1969 JRR Tolkien finally sold the film and merchandising rights of The Lord of the Rings to United Artists for approximately £104,000. A year later the studio asked director John Boorman if he could make the books into a viable film. Boorman, an established director with a track record of being experimental, set about developing a screenplay with his long term collaborator, Rospo Pallenberg. What emerged was a one hundred and fifty minute script and possibly the most radical adaptation of Tolkien's work. Some of the ideas and concepts it contained were extremely innovative but others where simply too radical a divergence from the source text. I’ve collated a few of these for your consideration. If you are familiar with Boorman's 1973 film Zardoz, then you will note both similarities and re-occurring themes.

In 1969 JRR Tolkien finally sold the film and merchandising rights of The Lord of the Rings to United Artists for approximately £104,000. A year later the studio asked director John Boorman if he could make the books into a viable film. Boorman, an established director with a track record of being experimental, set about developing a screenplay with his long term collaborator, Rospo Pallenberg. What emerged was a one hundred and fifty minute script and possibly the most radical adaptation of Tolkien's work. Some of the ideas and concepts it contained were extremely innovative but others where simply too much of a divergence from the source text. I’ve collated a few of these for your consideration. If you are familiar with Boorman's 1973 film Zardoz, then you will note both similarities and re-occurring themes.

1.) After the destruction of the Ringwraiths at the Fords of Bruinen, Frodo is carried into the sparkling palace of Rivendell, where in a vast amphitheatre full of chanting Elves he is laid naked on a crystal table and covered with green leaves. A thirteen-year-old Arwen surgically removes the Morgul-blade fragment from his shoulder with a red-hot knife under the threatening axe of Gimli, while Gandalf dares Boromir to try to take the Ring.

2.) The narrative of "The Council of Elrond" was to be visually interpreted as a fantastic medieval masque representing the history of the Rings. It was to combine elements of Kabuki theatre, rock opera, and circus performance.

3.) At the gates of Moria, the fellowship bury Gimli in a hole, throw a cape on him and beat him to a state of utter exhaustion to retrieve his unconscious ancestral memory. This ancient knowledge allows Gimli to recollect the word for entering Moria and gain insights about the ancient dwarf kingdom.

4.) Also in the Moria sequence, the orcs are slumbering or in some kind suspended animation. The fellowship runs over them and the rhythm of their footsteps start up their hearts.

5.) There was a proposed wizard’s duel between Gandalf and Saruman. This was inspired by an African idea of how magicians duel with words. The script reads:

Gandalf: Saruman, I am the snake about to strike!

Saruman: I am the staff that crushes the snake!

Gandalf: I am the fire that burns the staff to ashes!

Saruman: I am the cloudburst that quenches the fire!

Gandalf: I am the well that traps the waters!

6.) Perhaps the most provocative changes occur by introducing a sexual element. Not necessarily in a exploitative way but more of a metaphor exploring the nature of power. For example, before gazing into Galadriel's mirror, Frodo must have sex with her. Aragon's battlefield healing of Eowyn becomes a sexual analogy of the healing power of the king.

Needless to say, executives at United Artist failed to understand Boorman's script. The project was shelved indefinitely. When Ralph Bakshi approached the studio in 1976 with a proposal of adapting Tolkien's work in to an animated film, the script had to be purchased to acquire full artistic control. Boorman allegedly received $3,000,000 for his script. When Boorman later made his big screen adaptation of the Arthurian legend Excalibur in 1981, many parallels where drawn with The Lord of the Rings. It has often been suggested that several ideas from his the unused Tolkien screenplay made it in to that movie.